The animal behavior that undermines behaviorism

Instinctual drift and the failure of reinforcement

Keller Breland, a brilliant student of B.F. Skinner, has his finger on a button. (Or perhaps it was his wife Marian Breland, a brilliant student of B.F. Skinner – it appears she was first) As soon as the raccoon drops the coin into the piggy bank, Breland presses the button. A click sounds as the magazine releases a food pellet. The raccoon will eventually place the coins in the bank on stage, as part of an animal show.

The raccoon picks up another coin. But this time, the raccoon rubs the coin with his paws. How cute!

Raccoons engage in this behavior (dousing) in the wild because they often eat crayfish or other aquatic animals; they rub the shells off of their food.

But the raccoon keeps doing it. He won’t put the coin in the slot. He doesn’t get his food pellet. He doesn’t engage in the “reinforced” behavior.

Reinforcement can’t convince a racoon to drop a coin. It can’t defeat the natural behaviors of an animal. What could it possibly do for a human?

Noam Chomsky wrote one of the most famous critiques of behaviorism in the form of a 1959 review of Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior. In an interview with behaviorist Javier Virués-Ortega in 2006, he mentions the Brelands as evidence against the behaviorist model:

By the early 1960s, a couple of years after the review appeared, there was internal criticism which shattered what was left of the foundations of the subject. Two of Skinner's major students, Keller and Marian Breland, went off into animal training. They were the main animal trainers, they wanted to train all the things, circus animals and so on. What they discovered was that this was just not working [Breland & Breland, 1961]. I mean, the trainers, the psychologists, they were actually using the instinctive behavior of the animal and slightly modifying them by a training routine. But then, the animals were just drifting back to their normal instincts, to their behavior, refuting all the theory. It's what is called instinctual drift.

Chomsky refers to Breland & Breland, 1961. In The Misbehavior of Organisms, Keller and Marian Breland detail the aforementioned experience of instinctual drift of foraging behaviors with a raccoon; chickens that repeatedly scratch the ground; a pig who repeatedly pushes a coin with its snout; and a litany of smaller issues with certain animals (e.g., cats will not leave the area of the feeder, and rabbits will not approach it).

Of behaviorism, the Brelands write in their conclusion:

(Skinner, in the 1984 article The phylogeny and ontogeny of behavior, called the tabula rasa idea, as attributed to behaviorists, “a myth”)

The Brelands predicted that some behaviorists would qualify these behaviors as superstitious, as when coincidental behaviors are accidentally shaped or reinforced – for example, a pigeon may peck a lever, but also spin in a circle first, where spinning is not targeted. They seem to believe that when confronted with data that does not fit the behaviorist model, they will face an audience that dismisses their data.

But did the Brelands, when faced with data that did not fit within their model, prematurely dismiss their model?

According to Virués-Ortega, the Brelands had this to say:

Clearly the Brelands understood the power of positive reinforcement: they remained wildly successful animal trainers, despite occasional setbacks.

Their point was that they couldn’t explain this behavior, and at the time it didn’t seem like anyone else could either.

Skinner, in his previously mentioned article The phylogeny and ontogeny of behavior, addressed the Brelands directly.

The conclusion is plausible, however, and not disturbing. A shift in controlling variables is often observed. Under reinforcement on a so-called fixed-interval schedule, competing behavior emerges at predictable points (Skinner & Morse 1957).

Skinner & Morse is summarized thusly:

"When a rat is free to run in a low-inertia running wheel or to press a lever for food on a fixed-interval schedule, the resolution of the competition between running and pressing can be expressed in the following way. When the schedule normally generates a substantial rate of responding, running in the wheel is suppressed. When the schedule does not generate a substantial rate, running in the wheel occurs. Shortly after reinforcement, however, both behaviors are absent."

In this description, Skinner was ahead of his time.

A rat is provided access to food on a fixed interval schedule. Approximately every minute, one small food pellet is released into its cage. The session lasts 3 hours.

The rat, inexplicably, drinks 10 times as much as when it has free access to food and water.

A monkey is kept in an impoverished environment. Videos of other monkeys are delivered on a fixed interval schedule. The session lasts 1 hour.

The monkey, inexplicably, drinks 24 times as much as when it has free access to food and water.

The twist: we have an understanding of this phenomenon.

Excessive water intake is known as polydipsia and has been experimentally demonstrated as early as 1961.

The drinking itself is not reinforced, nor is it superstitious – it is induced by the very schedule of reinforcement. Behavior such as polydipsia is known as adjunct, or schedule-induced, behavior.

How can the schedule “induce” – essentially, trigger – a behavior?

In a 2012 article, William Baum begins, “The concept of reinforcement is at least incomplete and almost certainly incorrect.” He goes on to explain induction as a law of behavior. Essentially: when two events are paired in the environment, such as food delivery and pressing a lever, each can serve as an SD for the other. How that works in practice: a rat presses a lever and food is delivered. A period of extinction eventually leads the rat to stop pressing the lever. Food is delivered. The rat begins to press the lever – reinforcement preceding behavior, in an inversion of how it is commonly understood.

The token and the food reinforcer become associated in the environment, for the raccoon. The token triggers food-related behavior.

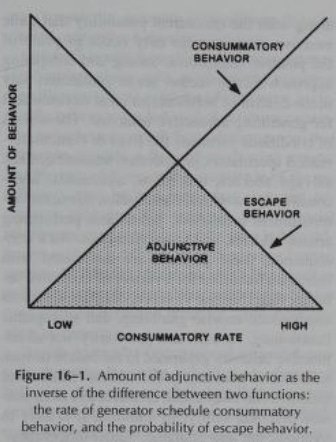

Falk, who demonstrated polydipsia in 1961, returns to adjunct behavior in a 1998 chapter of a book entitled Learning and Behavior Therapy. Adjunct behavior is reliably triggered when delivery of a highly valued reinforcer is on a noncontingent fixed interval schedule. Interestingly, the reinforcer delivery cannot be too much or too little. What if escape (from a thin schedule) and reinforcement, essentially, compete?

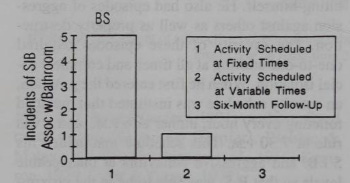

Falk experimentally demonstrated, in a human subject, SIB occurring at a high rate directly after a fixed interval delivery of bites of ice cream. Other demonstrated adjunct behavior in humans include excess grooming, smoking, movement, drinking, and even aggression. In humans, could it be that we see some adjunctive problem behavior directly after providing reinforcement?

He concludes with a stunning illustration: an institutionalized man with high rates of SIB was on an activity schedule, a very typical intervention. When his fixed time schedule was switched to a variable time schedule of activities (e.g., scheduled hygiene within a 1 hour time window instead of at a specific time), his SIB reduced significantly.

Murray Sidman wrote an article in 1960, the year prior to the Breland article, entitled Normal Sources of Pathological Behavior. Skinner (and Estes) had discovered, in 1941, that a warning tone before an unavoidable shock suppressed lever pressing – despite the fact that lever pressing and shock were not related behaviorally (only temporally). Further, if the lever press delivered food or water, not pressing meant that animals did not receive the maximum amount during the session time. (Long-term exposure to a drug, reserpine, “cured” suppression, an intriguing illustration of pathologizing an environmental condition.)

Sidman started with this “conditioned suppression” phenomenon. Through trial and error, in changing schedules of shock and reinforcement, Sidman evoked unexpected behavior. Nevertheless, each time the behavior patterns changed, they were under the control of the schedule, and could be replicated. The final word, from Sidman:

Out of our investigations, then, there emerged a new appreciation of the behavioral complexities with which we had been working. Our first attempts to unravel these complexities seemed to multiply them, producing behavior which, if not pathological, was certainly bizarre, but we were eventually able to show that even the most bizarre performances were under the control of orderly and manipulable factors. In no sense did they represent deviations from lawful behavior.

I enjoyed reading your article. Reminds me of the coursework I took with Peter Killeen.

Wonderfully done account of how behavior that evokes magical explanations is actually lawful, Fred. Thanks!